Disclaimer: These essays presume you’ve seen the film in question. If you want to avoid spoilers, watch the movie first!

Ugh.

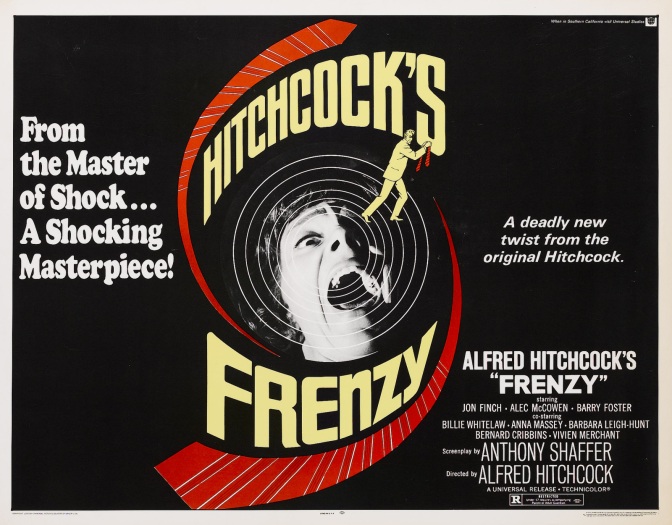

Well, here we go. Frenzy was made in 1972. It Hitchcock’s second-to-last film and his conscious attempt to make a movie that was more graphic and explicit than anything he’d ever done. It contains his most brutal onscreen murder, a graphic rape and strangling of a woman, as well as several other dead women and desecrated corpses. Hitchcock had killed plenty of men and women before, but never like this.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with making a film about the murder of women, or the brutal rape of women, or anything in between. I firmly believe that no topic should be taboo for art, depending on how it’s handled and what the artist is trying to communicate.

But it’s the endless repetition and attrition. How many films or TV shows have you see that focus on serial killers of women? That show their killing or rape in graphic detail. Now, how many can you think of that show graphic rape or murder of men? They’re out there, for sure, but it’s much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much rarer.

Women brutally murdered on camera is the norm. That’s a horrible fucking sentence. Sometimes it’s done for art. Sometimes it’s done to show how brutal men can be. Sometimes it’s done to show how awful rape is. Sometimes it’s done for fun. Sometimes women are raped or sodomized and it’s all a big joke (I’m looking at you, Quentin Tarantino).

How many women have been killed and/or raped onscreen? It starts to get to the point where it doesn’t matter. You can be Gaspar Noé making Irreversible or Jonathan Kaplan making The Accused or Alfred Hitchcock making Frenzy or any one of a thousand other films that seek to “educate” or titillate and it just doesn’t fucking matter. Graphic rape and murder scenes will always be there, and at this point in film history they’re simply offensive. And more than that, they’re pointless.

The example of violence in movies I always return to is in Werner Herzog’s documentary Grizzly Man (If you haven’t seen it, put down this essay and watch it now). In the film, Herzog is on camera as he listens to the last footage of bear “expert” Timothy Treadwell, who was killed by the grizzly bears he loved and tried to protect. One of Timothy’s friends has his videocamera that has actual audio of him being attacked and killed. Herzog steels himself and listens to it on headphones.

Herzog is visibly shaken, and asks the woman if she has ever listened to it. She says no, and he replies that “you must never listen to this.” We never hear the tape. We only see her reaction to Herzog as he listens. Not only is this the proper, human thing to do, it’s also the better choice for the film. Whatever we imagine is a thousand times worse that whatever garbled mess Herzog heard.

As a counter example, look at the 2015 film Bone Tomahawk, a “cannibal western” that’s actually much more elegant and thoughtful than that moniker would suggest. Until a climactic scene where the cannibals kill and literally split a man in half. It’s an impressive piece of special effects work, but it’s so over-the-top, so grisly, that it means nothing. It cheapens the dignity of the film and turns an other good movie into a special FX footnote (“Dude, did you see that movie where they split a guy in half??”).

Back to Frenzy. I hadn’t seen this film in years; it’s not the type of movie you revisit. Still I remember enjoying it, considering as most critics do, a return to form for Hitchcock after the disappointments of Torn Curtain and Topaz.

Hitchcock had initially planned a completely different film titled Frenzy, inspired by the Michelangelo Antonioni of all people. It was in the style of Blow-Up, a sexually explicit thriller about a young woman who falls in love with a man only to realize he’s a serial killer. After Hitchcock make it clear how graphic and experimental the movie would be, nervous Universal executives pulled the plug and Hitch instead made the underwhelming Topaz.

But those ideas were still rattling around in his head when he set out to adapt Arthur La Bern’s serial killer novel Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square. He would repurpose the title, Frenzy, and enlist playwright Anthony Shaffer (who also wrote Sleuth and The Wicker Man). Hitchcock was determined to force his own ideas onto the existing plot, maybe too many ideas at once because Frenzy is a tonal mess. The film jumps from plot to plot, introduces and abandons characters & themes, and perhaps even more than Marnie, is completely contemptible towards women. It’s nasty, brutish, and unfortunately not short.

There are kernels of good ideas here, as when Hitch makes the leading character a disagreeable drunk and hothead who’s impossible to like, while the serial killer is a charming man about town. But the film shifts wildly from the man wrongly accused of the killings to his girlfriend, to the killer, to the police detective and back and forth. There’s no chance to build identification, the way we do in Psycho, spending time with each character.

There’s a point early on when I almost turned the film off. The leading man, Jon Finch, has just been fired and is aimlessly hanging out in a pub when two barristers come in to discuss the “Necktie Killer” who is terrorizing London. First there’s a lot of psychological pseudo-babble intended to educate the audience, much like the psychologist at the end of Psycho. And then we’re treated to this exchange about the killer:

BARRISTER 1: “He rapes them first?”

BARRISTER 2: “Yes, he does.”

BARRISTER 1: “Well, suppose it’s nice to know that every cloud has a silver lining.”

That last line is said to the female bartender, who laughs it off with an “oh, you” look.

But I gritted my teeth and tried to give Hitchcock the benefit of the doubt here. As the scene ends, one of the Barristers comments that killers are good for the tourist trade, and “we haven’t had a good juicy series of sex murders since Christie [a serial killer who was tried and hung in 1953].”

Soon after this, we see one of these rapes and murders in graphic detail. Barry Foster goes to Barbara Leigh-Hunt’s “Friendship and Marriage” agency to be matched with a woman, only to be told that they can’t find a woman who matches his “certain peculiarities.” He reacts violently and attempts to rape her, but his impotence infuriates him and he strangles her with his necktie. It’s a shocking, uncomfortable, explicit scene that’s the inverse of the killing in Psycho: we see it coming, and we know what’s going to happen. Foster pulls down her shirt to expose her breasts, which she tries to cover up. When he snaps and strangles her, it’s sudden and upsetting, a true act of male violence. There’s no art to it, just uncomfortable exposure and dull, flat lighting.

If Hitchcock had stuck to this idea of deconstructing the quaint British preoccupation with murder, Frenzy might have been something great. By contrasting the sly, jokey “locker room” talk of the barristers with the cold hard reality of rape, Hitch could have made a point about toxic male sexuality and the cost of human life.

But Frenzy does away with this juxtaposition and destroys any good will it might have earned. When Finch’s girlfriend is killed, Foster dumps her body in a truck full of potato sacks, but then realizes she grabbed his tie pin in the struggle. Foster jumps into the truck in an attempt to retrieve his incriminating tie pin, prying it from her lifeless fingers in a scene that Hitchcock has the gall to play as comedy.

To be clear, there’s something to be said for trying to make the audience empathize with someone they normally wouldn’t; it’s the basis for Psycho, where for much of the film we’re rooting for Norman Bates to get away with it. But to play a scene where a killer is looking for a tie pin and keeps getting the dead woman’s foot stuck in his face, and when the truck slams to an unexpected stop the killer’s face ends up between the legs of the dead woman…well it’s too much for me. It undoes any of the commentary that Hitchcock established and makes me wonder if he ever intended it in the first place.

My suspicion had been that as Hitchcock’s wife Alma got sick later in life and backed away from an active role in filmmaking, Hitchcock’s black edge toward women had sharpened. But sadly that’s not true; there are detailed records of Alma and Hitch working on the first treatment of Frenzy, which was equally sexually explicit and cruel. It’s hard to compare this crass, exploitative filmmaker with the director who made “women’s pictures” and cared for his female heroes in dozens of pictures. Who’s the real Hitchcock?

Yes, there are good things about the movie. Hitchcock spent much of his childhood in Covent Garden with his shopkeeper father, and the film has a lovely affection for this place. It’s nice to see Hitchcock working in England again after decades away. And it also contains his last show-stopping shot: The killer leads a woman into his second-floor flat and closes the door. The camera retreats slowly down the stairs, backing down and around a corner and down a hallway (shot on a soundstage – watch for a part of the doorjamb to slide into place after the camera had passed through), before finally moving into the street in a miracle of cutting and matching on action. Hitchcock cuts from the soundstage when a man with a bag of onions passes in front of the camera, to an identical exterior in Covent Garden. The invention of the Steadicam a few years later would render such ingenuity unnecessary, but for now it’s an eerily effective shot.

There are other nice moments too, like the police detective who talks over the case with his wife during dinner (and a bizarre bit of comedy where she offers a guest a “Mar-gar-ita” made with “Te-Kwee-La”). But does it matter how pretty the box is when it’s full of shit?

The truth is that I’m tired. Tired of it all.

I could tell you that this hits close to home for me because I know women who were brutally assaulted by men. But I shouldn’t have to. It shouldn’t be a personal requirement that you know a woman who was raped or killed by a man to feel empathy for them onscreen. We shouldn’t want to see this on screen for a thousand, million different reasons but mainly because we’re long past the point there it adds anything to a movie. It’s never shocking, and it’s never clever. At this point it’s torture porn, or the same impulse that makes Quentin Tarantino use the n-word in as many of his scripts as possible, because stupid straight white men want to find ways around the rules.

I’m fucking done with it, like I’m done with Donald Trump bragging about grabbing a woman’s pussy and kissing whoever he wants. It’s not fucking okay.

I’ve talked a lot about how this Hitchcock 52 project is draining me and how I don’t know if I can keep going. This is the closest I’ve come to stopping, and it was a real crisis of faith for me last night.

But I guess that’s what it means to grapple with art. As much as I love Hitchcock and want to keep loving him, the grim exploitative darkness of this film really soured me. And I still haven’t watched Psycho or The Birds. I’m aiming to finish this. I hope I can.

Frenzy is not streaming on any services, but can be rented on Amazon or iTunes, or rented from your library.

Arrived here after hearing a BBC story on Frenzy. I haven’t ever seen it (have enough trouble with his treatment of women in his earlier films, jesus) so I wanted to read some discussion of the rape. It sounds just as horrible as I expected, but your piece is a pleasure to read — I appreciate both your analysis and your honest emotion, as well as the unexpected connection to Herzog of whom I’m a massive fan. Glad I stumbled upon your writing.

LikeLike